Researchers at Cornell University have created cell-size robots that can be powered and steered by ultrasound waves. Despite their tiny size, these micro-robotic swimmers – whose movements were inspired by bacteria and sperm – could one day be a formidable new tool for targeted drug delivery.

For more than a decade, Mingming Wu’s lab has been investigating the ways microorganisms, from bacteria to cancer cells, migrate and communicate with their environment. The goal was to create a remotely controlled micro-robot that could navigate in the human body.

Wu’s team initially tried to design and 3D print a micro-robot that mimicked the way bacteria use flagellum to propel themselves. However, like the early aviators whose cumbersome airplanes were too bird like to fly, that effort collapsed. Soon, they began exploring a less literal approach. The primary hurdle was how to power it. As a person must crawl before they can walk, a micro-robot needs to be energized before it can swim.

“Bacteria and sperm basically consume organic material in the surrounding fluid, and that is sufficient to power them,” Wu said. “But for engineered robots it’s tough, because if they carry a battery, it’s too heavy for them to move.”

The team hit upon the idea of using high-frequency sound waves. Because ultrasound is quiet, it can be easily used in an experimental lab setting. As an additional bonus, the technology has been deemed safe for clinical studies by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

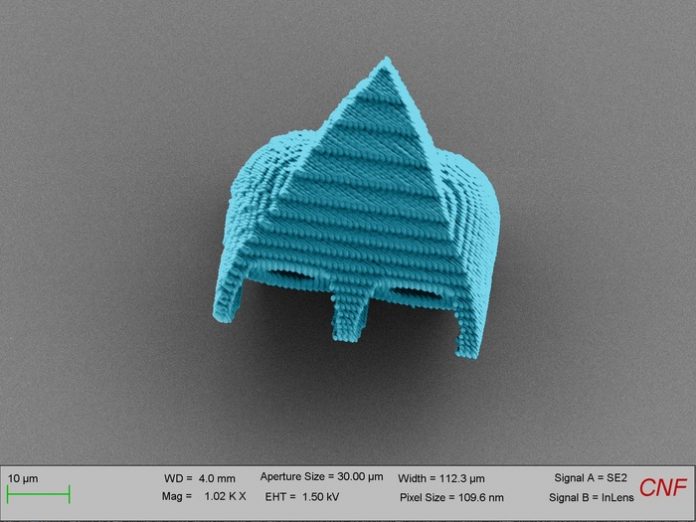

Working with the Cornell NanoScale Science and Technology Facility (CNF), former postdoctoral researcher Tao Luo created a triangular micro-robotic swimmer that looks like an insect crossed with a rocket ship.

The swimmer’s most important feature is a pair of cavities etched in its back. Because its resin material is hydrophobic, when the robot is submerged in solution, a tiny air bubble is automatically trapped in each cavity. When an ultrasound transducer is aimed at the robot, the air bubble oscillates, generating vortices – also known as streaming flow – that propel the swimmer forward.

Other engineers have previously built “single bubble” swimmers, but the Cornell researchers are the first to pioneer a version that uses two bubbles, each with a different diameter opening in their respective cavity. By varying the sound waves’ resonance frequency, the researchers can excite either bubble – or tune them together – thereby controlling which direction the swimmer is propelled.

The challenge ahead will be to make the swimmers biocompatible, so they can navigate among blood cells that are roughly the size as they are. Future micro-swimmers will also need to consist of biodegradable material, so that many bots can be dispatched at once. In the same way that only a single sperm needs to be successful for fertilization, the volume is key.

“For drug delivery, you could have a group of micro-robotic swimmers, and if one failed during the journey, that’s not a problem. That’s how nature survives,” Wu said. “In a way, it’s a more robust system. Smaller does not mean weaker. A group of them is undefeatable. I feel like these nature-inspired tools typically are more sustainable, because nature has proved it works.”

The paper published in Lab on a Chip, a publication of the Royal Society of Chemistry.