[ad_1]

It is a fight for Turkey’s future.

So much is at stake in Sunday’s presidential election that the country’s electoral board reports nearly half of the three million Turks living outside the country have already marked their ballots. It is a record turnout.

In Toronto, lineups snaked around the Turkish consulate for three days of advanced voting. Ekrem Alpaydin had the Turkish flag wrapped around his shoulders. He sees only Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the current president, in Turkey’s future.

“He’s the best leader in the world — seriously, honestly,” Alpaydin said. “My leader is strong.”

Others in the voting line rolled their eyes, with one shouting, “He’s a f—ing dictator!”

Ezgi Ulkuseven wouldn’t reveal who she was choosing, but said, “I’m not supporting Erdogan, I can tell you that.”

“I think a lot of people are angry about the way things are in Turkey right now, so [this vote] could change a lot of things.”

Much of the anger is tied to Turkey’s troubled economy, the country’s involvement in the Syrian war and the reality of housing millions of refugees.

The country is also still under a state of emergency nearly two years after the deadly attempt to topple Erdogan’s government. In the ensuing crackdown, more than 150,000 people have either lost their jobs or are in prison awaiting trial.

Whatever the election result, it will be life-altering for the country’s nearly 80 million people and have lasting ramifications for Turkey’s neighbours and allies.

Canada is already a popular safe harbour for Turks from the recent tumult. The number of Turkish asylum seekers in Canada quintupled in 2017. Thousands of others are coming as students, permanent residents or investors.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat’s at stake?

This weekend’s vote could lock in a new presidential system for Turkey — one that Erdogan has pushed for.

It has been billed as similar to the U.S. presidency, but critics worry it will have fewer checks and balances than Turkey’s parliamentary system, and will write a blank cheque for an already powerful leader. After 15 years leading the country, Erdogan could win at least another decade in power.

But this time, Erdogan is up against some of the strongest opponents he has ever faced.

Meral Aksener, in red, is one of the founding members of Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party, and now leads Turkey’s Iyi (Good) Party. (Jeff Mitchell/Getty Images)

Some are emulating his cadence, his shout and populist touch while promising significant change — and at the top of the list is relaxing the grip he’s held on freedom of expression.Erdogan’s recent anti-West, anti-EU rhetoric has rattled allegiances with the U.S. and Europe, fueling fear that the West could lose a key, calm friend in the region.

Four of the Turkish parties running in the election are willing to cobble together a coalition — despite the political and ideological chasms between them — because they share the singular goal of ending the Erdogan era.

Erdogan’s opponents

Muharrem Ince is seeing a remarkable swell of support as head of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). Ince’s popularity has clearly swayed Turkish media.

Out of fear of or outright support for Erdogan, opposition voices usually get minimal play. Now, media outlets are carrying Ince’s events and inviting him into their studios for live interviews — although Erdogan is still getting the bulk of airtime.

Ince is a former teacher, and one of his most colourful proposals is to turn Erdogan’s extravagant 1,150-room presidential palace into an education centre.

Muharrem Ince, the leader and presidential candidate of Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party, has garnered large crowds for his campaign rallies. (Ali Ege/AFP/Getty Images)

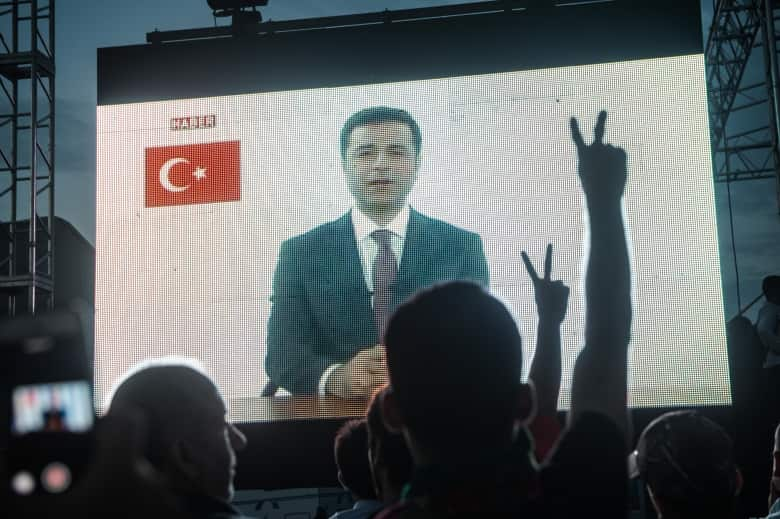

Selahattin Demirtas, the leader of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), is campaigning from his prison cell. He’s been there since 2016, accused of supporting terrorism.

Charismatic and, at 44, the youngest of the candidates, Demirtas made big gains in the 2015 election, passing the threshold to enter parliament. Soon after, Erdogan began alleging Demirtas was a supporter of the PKK, the Kurdish militant group behind a deadly insurgency in Turkey since the 1980s. It is an allegation Demirtas and the HDP have always denied, insisting it is politically motivated.

Meral Aksener, a sharp-tongued nationalist and one of the founding members of Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), is leading a new party, IYI, which promises a new future for Turkey. Savvy social media targeting of young Turks has been a key part of her campaign.

Temel Karamollaoglu is a UK-educated former engineer leading the small Saadet (Felicity) Party, which is attracting more religious voters disillusioned with Erdogan’s leadership.

The issues

The economy is one of the issues that initially helped propel Erdogan to power, and now it is what could hurt him most.

After years of economic growth and success under Erdogan, the reality now is a critically low lira, rising inflation and unemployment, particularly among young people. Nearly 11 per cent of people in the country are out of work, and recent numbers show nearly 20 per cent unemployment among people aged 15-24.

Supporters of Selahattin Demirtas watch the presidential candidate of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party speak via video from a prison cell. (Yasin Akgul/AFP/Getty Images)

At a recent election rally, Erdogan said rising refrigerator sales in Turkey were a sign of how well the economy was doing. Opponents seized on the moment — it was clear proof, they shouted, that Erdogan is out of touch.

Turkey’s complicated relationship with its Kurdish population is also a defining factor in this vote. While Turkey is still locked in conflict with the PKK — a group internationally recognized as a terror organization — Erdogan enjoys high support among conservative Kurds.

Turkey’s role in Syria and the three and a half million Syrian refugees now in Turkey are factors swaying voters, too.

In Toronto, student Yagmur Teze bristled at those issues, even as she talked about freedom for Turkish dissidents and minorities.

“Scholars, doctors, political leaders — everyone who is against [Erdogan] is now in jail,” she says. “Those people are now guaranteed rights to vote.”

Turkish officials said this week that 30,000 Syrian refugees are eligible to vote.

Pollsters are warning the final tally will likely be close. There are already plans for a potential second round of voting.

[ad_2]