[ad_1]

Entering into the Art Gallery of Ontario’s new exhibition Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak, “is like you are on Inuit homeland,” says artist Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory.

The Toronto gallery’s major exhibition this season juxtaposes the work of world renowned artist Kenojuak Ashevak with that of her nephew Timootee (Tim) Pitsiulak, highlighting two generations of artists from the celebrated artistic community of Kinngait, Nunavut.

“I realize that many Canadians may not necessarily be immediately able to recognize them,” said Williamson Bathory, a contributor to and co-curator of the exhibit.

“In artistic terms, these are our great grandparents, our grandparents. They opened up a path for us all to be able to continue to be creative, imaginative people.”

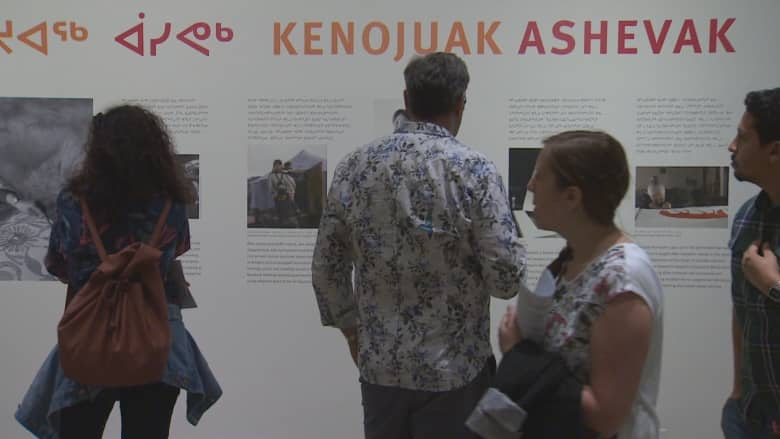

Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak was warmly welcomed by members of the public on June 13. (CBC)

Warmly welcomed by members of the public on June 13, at an opening ceremony that included a traditional preparation and sharing of seal meat, the exhibit is the AGO’s first by its recently revamped department of Canadian and Indigenous Art — a body that has been in the spotlight since its establishment last fall.

In October, the AGO’s efforts at inclusion came under scrutiny. At the same time as it announced the renaming and restructuring of its Canadian art department to include Indigenous artists, the former head of that very department published a column criticizing art institutions for not going far enough to truly remake themselves as representative, inclusive spaces open to new voices.

Then, this spring, the AGO sparked a vigorous debate over art history and cultural sensitivity when it announced it was changing the name of an Emily Carr painting to remove the word “Indian” from the title — as part of a wider effort to eliminate culturally insensitive language.

Being under this intense microscope feels “tremendous,” says Georgiana Uhlyarik, the AGO’s curator of Canadian art, who jointly leads the gallery’s Canadian and Indigenous Art department with Wanda Nanibush, its curator of Indigenous art.

“To me, the art museum is a place that invites very difficult conversations,” she said.

‘The art museum is a place that invites very difficult conversations,’ says Georgiana Uhlyarik, AGO curator of Canadian art and co-leader of the gallery’s Canadian and Indigenous art department. (CBC)

A byproduct of the controversy is that many more visitors have been making a beeline to see the “gorgeous, unbelievable” Carr painting, now listed under the name Church at the Yuquot Village, and asking more questions about it, Uhlyarik said.

“This is a moment where we have to listen, we have to figure out a way to move forward and we have to figure out a way to be respectful and trusting of each other. And that only comes with time.”

A byproduct of the controversy over the renamed 1929 Emily Carr painting is that many more visitors have been making a beeline to see it, Uhlyarik said. (B.C. Archive/B.C. Royal Museum, Art Gallery of Ontario )

‘Filling in’ art history

Canadian arts institutions have been gradually working toward more accurately showcasing underrepresented groups, like women and Indigenous artists, for more than a decade, according to Gerald McMaster, a professor at the Ontario College of Art and Design and a veteran Indigenous art curator.

By bringing Indigenous art under the umbrella of Canadian art, the AGO is drawing “attention to the fact that we have this rich history and drawing attention to the fact that Indigenous peoples have been here for thousands of years. It brings to light something that has been missing… They are slowly filling it in,” he said.

The AGO’s decisions are pulling people into discussions about Canada’s relationship with the Indigenous community and that’s exactly what art museums should be doing, McMaster added.

“Art museums are a place to debate, to bring controversy, because those are kind of safe spaces that we engage in as a society. We can openly look at these questions, these ideas,” he said.

“I think it opens up new ways of looking at the world and examining just who we are.”

A visitor to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto examines an artwork at the new exhibit Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak. (CBC)

Williamson Bathory says her hope is that the Tunirrusiangit exhibit will make Inuit art more familiar for visitors to the show and challenge them as well.

“I’m very excited that people, when they come through the exhibit, leave with more questions than they came in with,” she said, whether it’s about colonization, land rights, the residential school system or other important issues that continue to resonate.

“We are inviting people to look on to the strength and the beauty and the mysteriousness of what Kenojuak and Timootee are creating and feel empowered to go ask questions, to do research, to have conversations.”

[ad_2]