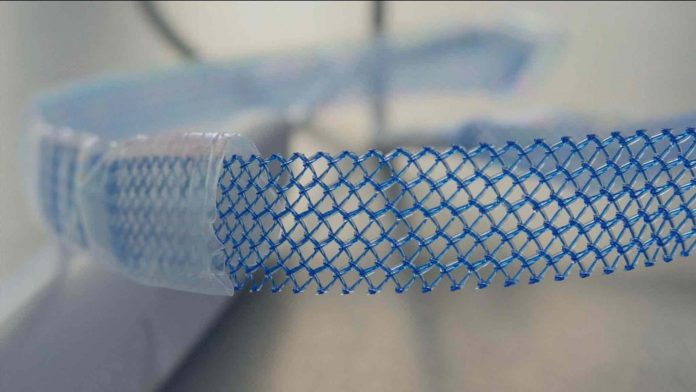

The use of vaginal mesh has been criticised in the past, due to the complications it can cause when it is put inside the body.

New guidelines from the health watchdog NICE published today will recommend that vaginal mesh surgery can be offered again by the NHS as long as certain conditions are met.

In July 2018 vaginal mesh procedures, used to treat incontinence in women, were halted as part of an independent safety review led by Baroness Cumberlege, days after she had spoken to women injured by mesh.

The aim of the moratorium was to allow conditions to mitigate the risk of injury to be put in place.

Thousands of women have suffered life-changing complications as a result of the procedure which is used to treat stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse brought on after childbirth.

The mesh implants are made out of plastic and designed to support weakened muscles like the bladder, or those that facilitate the functions of the vagina or bowel.

But some of the devices have cut through organs, caused permanent nerve damage and left some women unable to walk, work or have sexual relationships.

The highly anticipated guidelines from NICE, the first to be published in six years, will still offer mesh procedures as a second-line option after physiotherapy and once the pause on mesh surgery is lifted.

The guidelines also reintroduce the use of mesh for prolapse surgery which was banned in 2017.

In the documents, NICE said: “The benefits and risks of each type of treatment are laid out to ensure every women is fully informed. Where the evidence is limited, this is also highlighted.”

“There are a number of procedures recommended by NICE, including mesh procedures.”

This is despite the admission in the guidelines that evidence into the long-term harm of mesh is limited.

Dr Sohier Elneil, a leading surgeon in mesh removal, said she is surprised the NICE guidelines were published ahead of the conclusion of the Cumberlege review.

She said: “Having worked on reviews like this, the guidelines are not dissimilar to those of 2013. We have to bear in mind the complex issue we are facing and the fact we still do not know what the real complication rate is.”

“There is a huge amount of discussion in the guidelines and random trial but none that look into a large group of women.”

“We need to do a retrospective assessment of what has been happening over the last 20 years. In my opinion mesh needs to be something offered as a last resort, when everything else has failed.”

Dr Elneil receives around three hundred emails a day from women in distress, wanting help with a mesh complication.

“For me it has become a fight for justice,” she said.

“We have qualified the problem in a group of women but not quantified it for the general population. It’s a huge problem.”

Julie Gilsenan, 42, from Liverpool, had vaginal mesh surgery in 2017 to treat her mild incontinence.

She was immediately left in chronic pain and decided to undergo surgery to remove it, which is highly dangerous as the devices are designed to be permanent.

Julie’s condition is now worse than ever.

She can now longer work as a paramedic, is on the highest strength pain medication and struggles to get washed or dressed without the help of her husband.

She said: “I was running 5k a day before my surgery, and working long shifts as a paramedic.

“Now I spend most of my time on the couch.”

“Mesh has robbed me of my life.”

She added: “The pain wakes me up. It is in my hips, my groin and the front of my legs, it’s always there.”

“There is no let up.”

“I just wish I could go back, my life has totally changed. I want to be helping people, saving lives. I don’t want this to be my future.”

The independent review into the safety of Medicines and Medical Devices chaired by Baroness Cumberlege is due to report back later this year.