[ad_1]

OTTAWA — Seven First Nations spread out from Georgian Bay to Lake Scugog will decide this weekend whether to accept a $1.1-billion settlement from the federal and Ontario governments over a long-standing treaty dispute, the Star has learned.

Members of the Alderville, Beausoleil, Chippewas of Georgina Island, Chippewas of Rama, Curve Lake, Hiawatha and Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nations will vote on the proposed settlement Saturday.

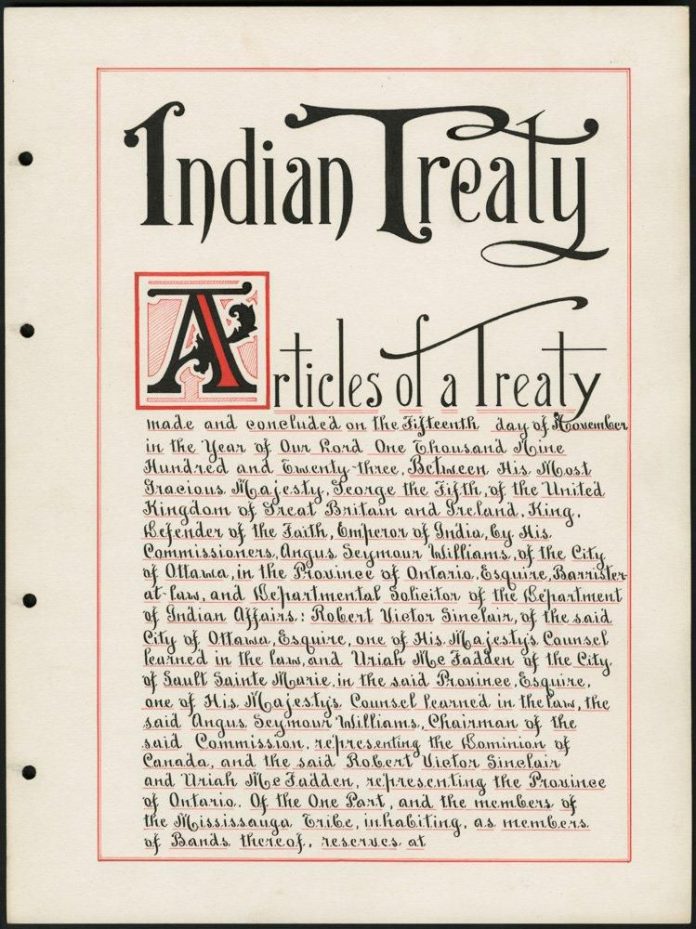

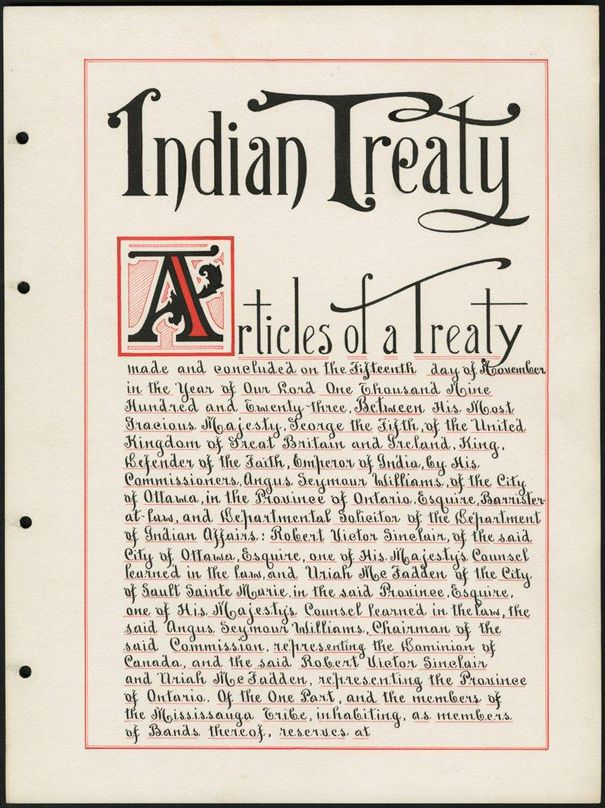

If approved, the deal would end decades of court litigation and negotiations over the controversial Williams Treaties from 1923. The First Nations have alleged for years that the Crown unjustly crafted and implemented these agreements without fair compensation for their land, and that the nations never surrendered fishing, hunting and other rights in the 20th-century treaties.

Chiefs from each of the First Nations either declined to discuss the proposed deal, citing confidentiality ahead of Saturday’s vote, or did not respond to interview requests from the Star this week. Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett’s office also did not respond to requests for comment on the proposed deal.

But documents obtained by the Star — labelled “privileged and confidential” — show details of the proposed agreement signed May 3, more than a year after Ontario, Canada and the First Nations announced renewed talks toward a settlement for Williams Treaties court cases that have languished since the early 1990s.

In a memo to the Curve Lake First Nation, Chief Phyllis Williams lays out the broad details of the potential deal: a total of $1.1 billion for the seven First Nations, and recognition of rights to hunt and fish on land from treaties signed before Confederation. Each nation would receive between $90.9 million and $98.7 million from the Canadian government, and between $60.6 million and $66.2 million from Ontario, according to the documents.

Williams’s memo also says the deal would grant 312 square kilometres of new land to the First Nations, and that both levels of government apologize “for having denied rights and appropriate compensation to our First Nations for nearly a century.”

The Williams Treaties — named for the government-appointed commissioner that oversaw the agreements — have been described by the federal government as “unique” in Ontario. This is partly because they dealt with lasting claims over huge swathes of land where treaties with Indigenous nations had never been signed, but also because they touched on existing deals from the early years of colonial settlement that were found to be inconclusive.

There’s also the fact that much of the land in question — north of Lake Ontario, roughly between Lake Simcoe and the Ottawa River — was already being developed by settlers, who by the early 20th century had built homes, mines and lumber mills on land that the Chippewas and Mississaugas had never agreed to relinquish.

“They’re one set of historic treaties that were signed very late,” said Jessica Orkin, a partner at Goldblatt Partners who specializes in Aboriginal law.

“When they got around to it in 1923, the land had already been used for a long time and there was people (living) on it.”

This was in violation of 1763 Royal Proclamation, a foundational tenet of British colonialism in North America that required agreement from Indigenous peoples in exchange for European settlement of their land, said Dan Shaule, an in-house historian with Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP, a Toronto-based firm that specializes in Indigenous rights and sovereignty.

Shaule explained that, while some treaties in the area were signed before Confederation, leaders from the First Nations tried repeatedly over several decades to start negotiations with the Crown for the unceded territory. But the provincial and federal governments were reticent to address the issue because of disagreement over who would compensate the groups for the land, he said.

“Generation after generation, they’re just turned away,” he said.

In 1916, the federal Justice Department learned through an internal investigation that some pre-Confederation treaties with the nations were problematic, a revelation that finally prompted Ottawa and Ontario to address the unceded territory and questionable previous deals at the same time. The result, Shaule explained, was two treaties inked in the fall of 1923, in which the seven nations received a lump sum of $500,000 — or $7.3 million at 2018 value — for massive tracts of land from Toronto’s Humber River to the Bay of Quinte, and north past Georgian Bay to the Ottawa River.

Unlike other treaties in Ontario and elsewhere, there were no annual payments or new reserve lands for the First Nations in the deal, and the governments held that rights to fish and hunt on the territory had been surrendered. The question of the status of these rights, as well as a dispute over whether the treaty commissioners promised an additional $230,000 — $3.3 million in 2018 — to the First Nations, fuelled disaffection with the treaties in the years since, Shaule said.

Concerns picked up after a Hiawatha fisherman was fined in the 1980s, prompting appeals over fishing rights all the way to the Supreme Court, which helped prompt the First Nations to launch court cases over the deals against Canada and Ontario in the 1990s, Shaule said.

Senwung Lu, a lawyer at the same firm as Shaule, said the court cases also dealt with issues like whether the First Nations surrendered rights over their burial sites — a point that was argued in an Ontario court in 2006, he said. Resolving such sensitive points are part of the reason it’s important to revive old treaties that have been described for years as unfair, said Lu, who argued that existing treaties in much of Canada need to be revisited.

“It’s about a long-term willingness to live together and take into account each others’ needs, and to make sure that the relationship going forward is better than the relationship has been in the past,” he said.

TOP STORIES, DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX.

[ad_2]