A black hole nearly 8,000 light-years from Earth has been behaving strangely and astronomers are fascinated.

Though it was discovered in 1989, the V404 Cygni black hole first garnered global attention in 2015 when it brightened telescopes for two weeks as it consumed material from an orbiting star.

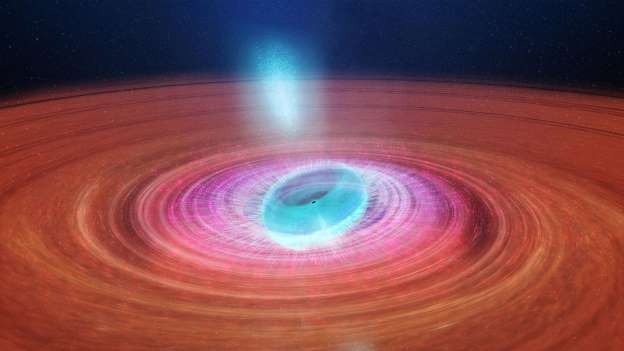

Not all of the matter was was consumed though, some of it, superheated by the gravitational force of the black hole, was shot far into space in bright jets of plasma.

While such outbursts are not out of the norm for black holes, usually they tend to emit from poles and go in the same direction.

However, a closer look at these jets revealed that instead they appeared to be firing in a wobbling pattern known as procession.

On Monday, in the journal Nature, James Miller-Jones, and his team of researchers from the International Center for Radio Astronomy Research in Australia, published their observations on the 2015 event and offered an explanation for V404 Cygni’s odd behaviour. The black hole is misaligned.

“We were gobsmacked by what we saw in this system — it was completely unexpected,” said the University of Alberta’s Gregory Sivakoff in a statement from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

The black hole itself is surrounded by a six-million-mile-wide disk of spinning matter known as an accretion disk. Generally, it is expected that the disk spins on the same axis as the black hole itself, but the strange pattern of the jets show that in V404 Cygni’s case it is not.

That misalignment was likely caused by the force of the supernova that created the created the Black Hole in the first place and combined with a phenomenon known as frame dragging it creates the spinning type like wobbling effect.

“This is the only mechanism we can think of that can explain the rapid precession we see in V404 Cygni,” Miller-Jones said. First posited by Albert Einstein as part of his general theory of relativity, frame dragging happens when the intense gravitational force of the black hole pulls space-time around it as it spins.

Prof Sivakoff said: “Finding this astronomical first has deepened our understanding of how black holes and galaxy formation can work. It tells us a little more about that big question: ‘How did we get here?’”