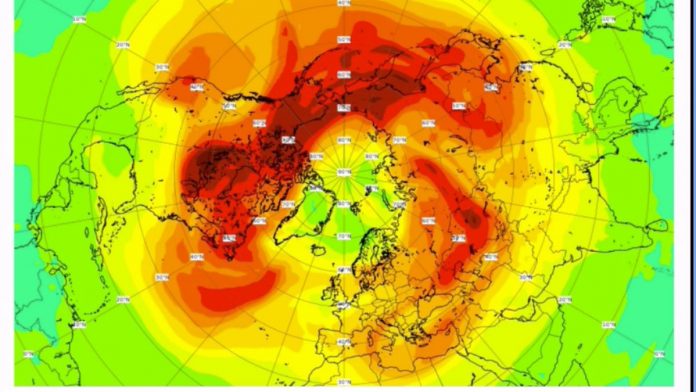

Several feel-good stories about the earth recovering have gone viral since the coronavirus pandemic forced the world indoors. Amid this, researchers have confirmed that the largest hole in the ozone layer over the Arctic region has closed in.

Researchers monitoring the “unprecedented” hole at the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS) announced the closure last week. Despite coronavirus lockdowns leading to a significant reduction in air pollution, researchers said the pandemic likely was not the reason for the ozone hole closing.

“Actually, COVID19 and the associated lockdowns probably had nothing to do with this,” CAMS tweeted Sunday. “It’s been driven by an unusually strong and long-lived polar vortex, and isn’t related to air quality changes.”

Now that the intense polar vortex has ended, the ozone hole has closed. CAMS said Monday that it does not expect the same conditions to occur next year.

The unprecedented 2020 northern hemisphere #OzoneHole has come to an end. The #PolarVortex split, allowing #ozone-rich air into the Arctic, closely matching last week's forecast from the #CopernicusAtmosphere Monitoring Service.

More on the NH Ozone hole➡️https://t.co/Nf6AfjaYRi pic.twitter.com/qVPu70ycn4

— Copernicus ECMWF (@CopernicusECMWF) April 23, 2020

According to recent data from NASA, ozone levels above the Arctic reached a record low in March. The “severe” ozone depletion was certainly unusual — 1997 and 2011 are the only other years on record when similar stratosphere depletions took place over the Arctic.

“While such low levels are rare, they are not unprecedented,” researchers said.

Human-made chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons have been destroying the layer for the past century, eventually causing the famous hole that formed in Antarctica in the 1980s. Experts pointed to “unusual atmospheric conditions” as the cause of the most recent hole, leading to industrial chemicals interacting with high-altitude clouds at abnormally low temperatures.