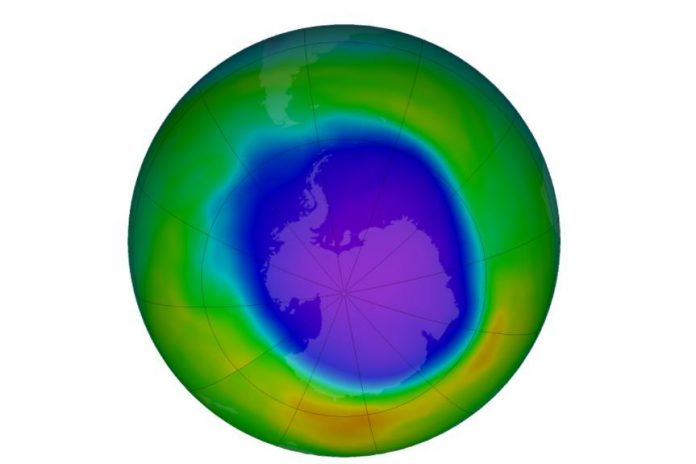

The annually occurring ozone hole over the Antarctic is one of the largest and deepest in recent years. Analyses show that the hole has reached its maximum size.

The 2020 ozone hole grew rapidly from mid-August and peaked at around 24 million square kilometres in early October. It now covers 23 million km2, above average for the last decade and spreading over most of the Antarctic continent.

WMO’s Global Atmosphere Watch programme works closely with Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service, NASA, Environment and Climate Change Canada and other partners to monitor the Earth’s ozone layer, which protects us from the harmful ultraviolet rays of the sun.

NASA’s Ozone Watch reports a lowest value of 95 Dobson Units recorded on October 1. Scientists are seeing signs that the 2020 ozone hole now seems to have reached its maximum extent.

“There is much variability in how far ozone hole events develop each year. The 2020 ozone hole resembles the one from 2018, which also was a quite large hole, and is definitely in the upper part of the pack of the last fifteen years or so”, Vincent-Henri Peuch, Director of Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service at ECMWF, said in a news release.

“With the sunlight returning to the South Pole in the last weeks, we saw continued ozone depletion over the area. After the unusually small and short-lived ozone hole in 2019, which was driven by special meteorological conditions, we are registering a rather large one again this year, which confirms that we need to continue enforcing the Montreal Protocol banning emissions of ozone depleting chemicals.”

The Montreal Protocol bans emissions of ozone depleting chemicals. Since the ban on halocarbons, the ozone layer has slowly been recovering; the data clearly show a trend in decreasing area of the ozone hole.

The latest WMO /UN Environment Programme Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, issued in 2018, concluded that the ozone layer on the path of recovery and to potential return of the ozone values over Antarctica to pre-1980 levels by 2060.

The large ozone hole in 2020 has beendriven by a strong, stable and cold polar vortex, which kept the temperature of the ozone layer over Antarctica consistently cold.

Ozone depletion is directly related to the temperature in the stratosphere, which is the layer of the atmosphere between around 10 km and round 50 km altitude. This is because polar stratospheric clouds, which have an important role in the chemical destruction of ozone, only form at temperatures below -78°C.

These polar stratospheric clouds contain ice crystals that can turn non-reactive compounds into reactive ones, which can then rapidly destroy ozone as soon as light from the sun becomes available to start the chemical reactions. This dependency on polar stratospheric clouds and solar radiation is the main reason the ozone hole is only seen in late winter/early spring.

Stratospheric ozone concentrations have been observed to have reduced to near-zero values over Antarctica around 20 to 25 km of altitude (50-100hPa), with the ozone layer depth coming just below 100 Dobson Units, about a third of its typical value outside of ozone hole events.

During the Southern Hemisphere spring season (August – October) the ozone hole over the Antarctic increases in size, reaching a maximum between mid-September and mid-October. When temperatures high up in the atmosphere (stratosphere) start to rise in late Southern Hemisphere spring, ozone depletion slows, the polar vortex weakens and finally breaks down, and by the end of December ozone levels have returned to normal.