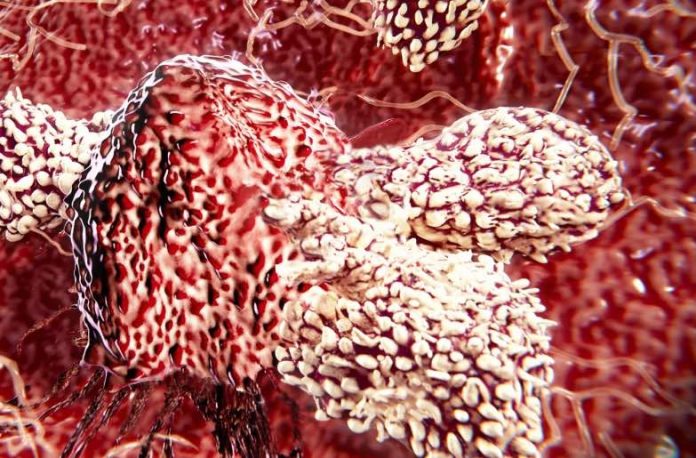

Researchers at Cardiff University have discovered a new type of killer T-cell that offers hope of a “one-size-fits-all” cancer therapy.

T-cell therapies for cancer – where immune cells are removed, modified and returned to the patient’s blood to seek and destroy cancer cells – are the latest paradigm in cancer treatments.

The most widely-used therapy, known as CAR-T, is personalised to each patient but targets only a few types of cancers and has not been successful for solid tumours, which make up the vast majority of cancers.

Cardiff researchers have now discovered T-cells equipped with a new type of T-cell receptor (TCR) which recognises and kills most human cancer types, while ignoring healthy cells.

This TCR recognises a molecule present on the surface of a wide range of cancer cells as well as in many of the body’s normal cells but, remarkably, is able to distinguish between healthy cells and cancerous ones, killing only the latter.

The researchers said this meant it offered “exciting opportunities for pan-cancer, pan-population” immunotherapies not previously thought possible.

How does this new TCR work?

Conventional T-cells scan the surface of other cells to find anomalies and eliminate cancerous cells – which express abnormal proteins – but ignore cells that contain only “normal” proteins.

The scanning system recognises small parts of cellular proteins that are bound to cell-surface molecules called human leukocyte antigen (HLA), allowing killer T-cells to see what’s occurring inside cells by scanning their surface.

HLA varies widely between individuals, which has previously prevented scientists from creating a single T-cell-based treatment that targets most cancers in all people.

But the Cardiff study, published today in Nature Immunology, describes a unique TCR that can recognise many types of cancer via a single HLA-like molecule called MR1.

Unlike HLA, MR1 does not vary in the human population – meaning it is a hugely attractive new target for immunotherapies.

What did the researchers show?

T-cells equipped with the new TCR were shown, in the lab, to kill lung, skin, blood, colon, breast, bone, prostate, ovarian, kidney and cervical cancer cells, while ignoring healthy cells.

To test the therapeutic potential of these cells in vivo, the researchers injected T-cells able to recognise MR1 into mice bearing human cancer and with a human immune system.

This showed “encouraging” cancer-clearing results which the researchers said was comparable to the now NHS-approved CAR-T therapy in a similar animal model.

The Cardiff group were further able to show that T-cells of melanoma patients modified to express this new TCR could destroy not only the patient’s own cancer cells, but also other patients’ cancer cells in the laboratory, regardless of the patient’s HLA type.

Professor Andrew Sewell, lead author on the study and an expert in T-cells from Cardiff University’s School of Medicine, said it was “highly unusual” to find a TCR with such broad cancer specificity and this raised the prospect of “universal” cancer therapy.

“We hope this new TCR may provide us with a different route to target and destroy a wide range of cancers in all individuals,” he said.

“Current TCR-based therapies can only be used in a minority of patients with a minority of cancers.

“Cancer-targeting via MR1-restricted T-cells is an exciting new frontier – it raises the prospect of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ cancer treatment; a single type of T-cell that could be capable of destroying many different types of cancers across the population.

“Previously nobody believed this could be possible.”

What happens next?

Experiments are under way to determine the precise molecular mechanism by which the new TCR distinguishes between healthy cells and cancer.

The researchers believe it may work by sensing changes in cellular metabolism which causes different metabolic intermediates to be presented at the cancer cell surface by MR1.

The Cardiff group hope to trial this new approach in patients towards the end of this year following further safety testing.

Professor Sewell said a vital aspect of this ongoing safety testing was to further ensure killer T-cells modified with the new TCR recognise cancer cells only.

“There are plenty of hurdles to overcome however if this testing is successful, then I would hope this new treatment could be in use in patients in a few years’ time,” he said.

Professor Oliver Ottmann, Cardiff University’s Head of Haematology, whose department delivers CAR-T therapy, said: “This new type of T-cell therapy has enormous potential to overcome current limitations of CAR-T, which has been struggling to identify suitable and safe targets for more than a few cancer types.”

Professor Awen Gallimore, of the University’s division of infection and immunity and cancer immunology lead for the Wales Cancer Research Centre, said: “If this transformative new finding holds up, it will lay the foundation for a ‘universal’ T-cell medicine, mitigating against the tremendous costs associated with the identification, generation and manufacture of personalised T-cells.

“This is truly exciting and potentially a great step forward for the accessibility of cancer immunotherapy.”

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, Health and Care Research Wales and Tenovus.

Professor Kieran Walshe, Director of Health and Care Research Wales, said: “We fund research that aims to make a real difference to people’s lives. This study is a significant development in the fight against cancer and it has the potential to transform the treatment of thousands of patients.”