Scientists at the University of Arizona have discovered the brightest known object in the early universe.

Xiaohui Fan, a regents’ professor of astronomy at UA, and his post-doctoral researcher, Jinyi Yang, discovered this object, brighter than 600 trillion of our suns, after Yang noticed an anomaly in raw data collected from a survey of the night sky.

“I saw a very bright 2-dimensional spectrum from our raw data, which we thought could be a very distant quasar,” Yang said.

The object, which they went on to observe, was, in fact, a quasar over 12.8 billion light years away.

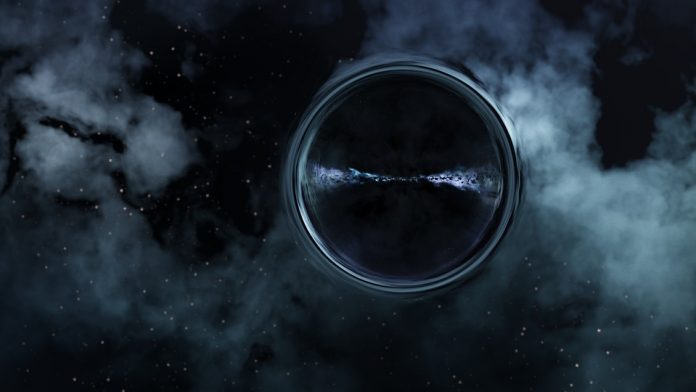

“A quasar, simply put, is the nuclei of a distant galaxy,” Fan said. “The extreme brightness comes from the dust and gas that is falling into the black hole at the center of the galaxy. As these particles collide, they heat up, and this process releases a humongous amount of energy, powering this beacon we can observe.”

The brightness of this quasar and its position in time, around 800 million years after the Big Bang, are extremely unique, according to Fan, and offer a rare opportunity to study the early universe.

This discovery was so unique, in fact, it caught the attention of the director of the Hubble Space Telescope, who fast-tracked Fan’s request to use the telescope to observe the quasar with much better resolution.

Gaining time to use the Hubble telescope is highly coveted and usually takes years, but Fan and his team were analyzing new data in mere months.

Fan and Yang discovered a galaxy is between Earth and this quasar.

“The massive gravitational force of this galaxy bends and splits the light from the quasar, acting as a magnifying glass,” Fan said.

This process, called gravitational lensing, magnifies the brightness of the quasar 50 times as it travels through time and space to reach Earth. Nevertheless, the quasar’s brightness is still unique in the early universe, which poses a number of questions for researchers.

Thanks to this gravitational lensing, researchers can get a much better view of what is surrounding the quasar’s black hole up to 150 light years away, an amazing resolution, according to Fan.

Fan and Yang’s future research will focus on studying these objects around the black hole and also what the black hole itself is doing and how it is growing.

Fan’s collaborators, which hail from 12 institutions across the world, have also been interested in Fan and Yang’s discovery. They plan to leverage this quasar’s light to study the evolution of the universe.

According to Fan, by carefully studying the light from the quasar, researchers can identify the density and temperature of the gasses it passed through on its journey to Earth, offering a window into the growth of the universe.

Due to the time and energy needed for objects like this to form, Fan believes this quasar and its black hole may be one of the older ones in the universe. Fan and Yang expect discoveries like theirs to get rarer and rarer as researchers peer deeper into the early universe.

Fan, who has been a professor and researcher at the UA since 2002, credits the university with helping catalyze world-renown astronomy research.

“UA is a center for astronomy in the world, because we have access to amazing facilities that we can use for these discoveries,” Fan said.

He and Yang have used telescopes from the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile to telescopes in Hawaii and even on Mt. Graham near Tucson during their research, in part thanks to UA’s investment in these facilitates.

Fan’s research, supported by the National Science Foundation and NASA, can be found in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.