Biomedical engineers and diabetes doctors from the University of the North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine and North Carolina State have developed an insulin patch that is capable of detecting increases in blood sugar levels and secreting insulin doses into the bloodstream when needed.

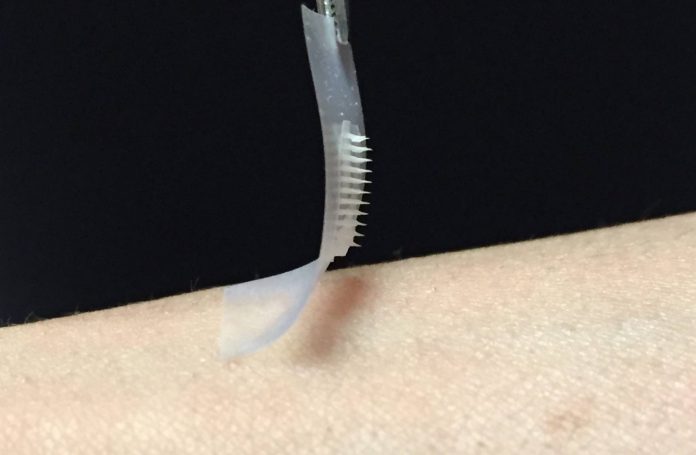

The patch is a thin square no larger than a penny. It contains more than 100 tiny needles that are approximately the size of eyelash. The “microneedles” contain microscopic storage units for insulin. The units contain enzymes that sense glucose levels and rapidly release insulin when blood sugar levels become too high. The microneedles penetrate the skin’s surface to tap into the blood flow through the capillaries just below the skin surface. In a mouse model of type 1 diabetes, the patch lowered blood glucose for up to nine hours.

“We have designed a patch for diabetes that works fast, is easy to use, and is made from nontoxic, biocompatible materials,” said co-senior study author Zhen Gu, PhD, a professor in the Joint UNC/NC State Department of Biomedical Engineering. “The whole system can be personalized to account for a diabetic’s weight and sensitivity to insulin so we could make the smart patch even smarter.”

While the approach does show great promise, researchers say that more pre-clinical tests and subsequent clinical trials are needed before the patch can be administered to human patients. “Injecting the wrong amount of medication can lead to significant complications like blindness and limb amputations, or even more disastrous consequences such as diabetic comas and death,” John Buse, MD, PhD, co-author of the study and the director of the UNC Diabetes Care Center.

Researchers gave one set of mice a standard insulin injection and measured blood glucose levels that returned to normal and then quickly rose into the hyperglycemic range. They tested another set of mice with the patch and observed that blood glucose levels were brought under control within thirty minutes and stayed level for several hours. The researchers also found that the patch could be fine-tuned to change blood glucose levels in a certain range by changing the dose of the enzyme contained in each microneedle. They found the patch was not as hazardous as insulin injections, which can cause blood glucose levels to plummet to dangerously low levels if administered too often.

“The hard part of diabetes care is not the insulin shots, or the blood sugar checks, or the diet but the fact that you have to do them all several times a day every day for the rest of your life, said Buse, the director of the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute and past president of the American Diabetes Association. “If we can get these patches to work in people, it will be a game changer.”

Researchers speculate that the patch’s ability to stabilize blood sugar in human patients could last longer than in mice because mice are less sensitive to insulin than humans. Gu said that their goal is to develop a smart insulin patch that only needed to be changed every few days.