People who live in cities face many challenges that threaten their mental health. In countries in which relatively higher numbers of people live in cities, depression, anxiety and addiction are generally more common. Amid the increasing incidence of common mental disorders and ongoing urbanisation around the world, there is an urgent need to better understand the dynamic interplay between these areas. This is what UvA researchers from the Centre for Urban Mental Health (UMH) say in their position paper, published on October 7 in The Lancet Psychiatry. The researchers emphasise the urgency of the situation and present a new conceptual framework for identifying novel prevention and treatment methods for common mental disorders in urban contexts.

Unintended disadvantages

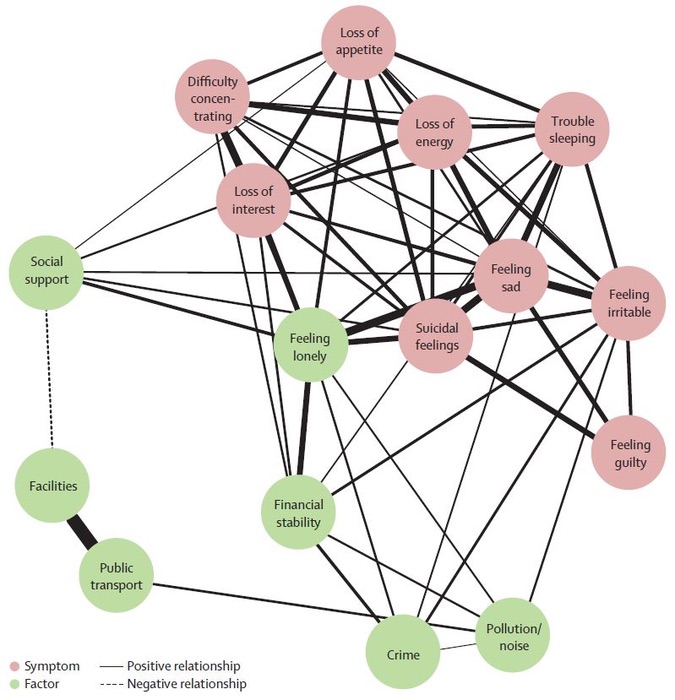

‘Life in the city is attractive in many ways, but it also has various unintended disadvantages,’ says lead author Junus van der Wal. ‘A great deal of knowledge has been accumulated about the extent to which these disadvantages in and of themselves are associated with mental disorders. But in order to really understand what living in a busy city does to your mental health, it is necessary to study all such factors together.’ In an extensive literature review, Van der Wal and his colleagues identified a large number of factors that influence the urban environment and, consequently, can also influence people’s mental well-being.

An example: the fictitious Jane

A sample scenario involving the fictitious Jane, given by the researchers in their position paper, makes it clear how different factors can interact and how important it is to look at the connection between factors. Jane lives in a big city, in a neighbourhood with little greenery. Her flat is close to a busy road. Jane has a low income, so she is often stressed about money. Constant traffic noise disturbs her sleep and causes insomnia. Her work performance is suffering as a result, which further increases her money stress. In addition, air pollution from the traffic on the busy road may affect the functioning of Jane’s brain. ‘Moreover, there are often feedback loops in these models. If many people in the area have mental health problems, for example, this can have a negative impact on the social cohesion of the neighbourhood, which in turn can have a negative effect on the residents,’ says Claudi Bockting, co-director of UMH and professor of Clinical Psychology within Psychiatry. ‘However, if the municipality where Jane lives were to invest in sustainable development, for example by creating a park between the building where Jane lives and the busy road, this could help Jane. This kind of intervention could reduce stress and traffic congestion, possibly increase social cohesion in the neighbourhood and help to counteract air pollution.’

Working towards targeted interventions

Reinout Wiers, professor of Developmental Psychopathology and co-director of UMH, adds: ‘In our position paper, we present a new conceptual framework for all future research on mental health in the urban environment. Only this approach will allow us to see how all the factors interact and affect individuals, and also to come up with targeted interventions and treatments to improve the mental health of urban dwellers.’

Karen Maex, rector magnificus of the UvA, is enthusiastic about the position paper: ‘It shows how our Centre for Urban Mental Health uniquely promotes the interdisciplinary cooperation that is essential for understanding the complex relationships between urban factors and mental health.’