Scientists have used MRI imaging to map visual brain activity in stroke survivors with sight loss that gives new hope for rehabilitation and recovery.

Scientists from the University of Nottingham have revealed new insights by combining data from clinical sight tests with brain imaging to precisely map the areas of the brain affected by sight loss. This allows identification of visual brain areas where function could potentially be improved with rehabilitation. The research, which was funded by the charity Fight for Sight has been published today in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Every year around 150,000 people in the UK have a stroke with roughly 30% experiencing some kind of sight loss as a result. Visual field loss is a common and devastating complication of cerebral strokes. This type of sight loss, called hemianopia, affects one side of a person’s vision and is caused by damage to the visual pathway in the brain.

A visual field test called perimetry is the current gold standard for measuring residual visual field coverage. However it has limitations. Its coverage is often coarse, it requires good attentional engagement of participants, and provides only indirect information about where in the visual pathway the key processing deficit is located. This limits the ability to identify potential strategies for visual rehabilitation – in terms of location in the visual field and the kinds of visual stimuli most likely to support recovery.

This new study combines detailed perimetry and multiple brain imaging datasets from four stroke survivors which shows that perimetry can be augmented with brain imaging data to provide a novel measure of residual visual field function. This combined approach provides potential for a personalized approach to therapy – guided by functional activity patterns in the post-stroke brain.

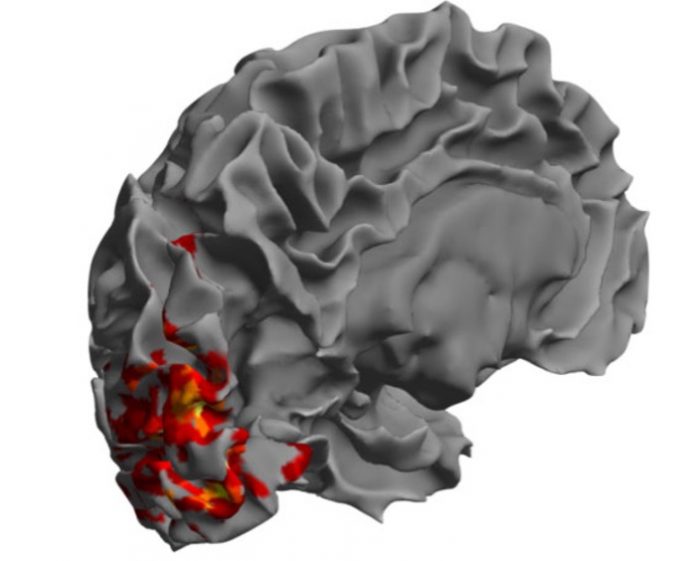

The research has been led by PhD student Anthony Beh from the University of Nottingham’s School of Psychology and supervised by Dr Denis Schluppeck, Dr Ben Webb and Prof Paul McGraw. Anthony explains: “A common misconception with stroke-related sight loss is that it affects vision through a particular eye. What is actually happening is that the eyes are seeing normally but the brain can’t process some of the information. This type of vision loss can be a particular problem for driving, reading or navigating a crowded space. It can also increase the risk of falls in older people. By exploring stroke-damaged brains with functional MRI and different kinds of visual stimulation, we found residual activity in the visual cortex, not detected by perimetry. This opens up possibilities for rehabilitation and offers new hope to stroke survivors.”

Dr Schluppeck adds: “By examining different types of brain scans we can actually see areas of ‘residual vision’ – places where the eyes and brain can still process images, even if this doesn’t reach awareness. Using MRI to pinpoint these areas of functional vision, clinicians could work with the stroke survivor and train them to recover some functionin that particular spot.”

The research also showed that the same visual field loss can be caused by very different patterns of brain damage. This highlights the need for individualised rehabilitation plans for stroke survivors.

Fight for Sight is the leading UK charity dedicated to stopping sight loss through pioneering research and funded this research project. Ikram Dahman, Chief Executive Officer (Interim) at Fight for Sight said: “This important research gives new and much-needed hope for people experiencing sight loss due to brain injury after a stroke. This work could truly be transformative in people’s recovery, helping to restore independence and improve overall quality of life. We look forward to the important outcomes of this study.”