[ad_1]

Cooper Hefner has his father’s translucent skin and mischievous smile, which stretches across his face like a flat line. He’s lankier but has the same eyes, impenetrable bits of brown seaglass below that high forehead.

“He looks just like his father,” marvels a woman catching a glimpse in a dark nightclub. True, if you can imagine Hugh Hefner without the satin pajamas and harem of spray-tanned blondes.

The comparison is inescapable because Cooper, 26, is the only Hef left in the family business. Which, of course, is Playboy.

In the nine months since Hugh’s death at 91, Cooper Hefner has stepped fully into his father’s role as the creative mind of a sprawling 65-year-old empire – cable channels, cocktail lounges, clothing and accessory lines and, of course, the flagship nudie mag.

The task at hand is daunting: to save one of the world’s most recognized brands from its own graying boomer-ness; from its slide into bunny mudflaps and other cheesy merchandise; from the ugly shadow of reality TV’s “The Girls Next Door.”

“We were producing twerking videos,” says Playboy’s chief executive Ben Kohn, as evidence of how far the brand had gone off the rails. But the identity crisis for new-era Playboy peaked in 2015, when the company abruptly concluded that it should no longer publish nudes.

Hugh Hefner (L) and Cooper Hefner attend the Annual Midsummer Night’s Dream Party at the Playboy Mansion hosted by Hugh Hefner on August 16, 2014 in Holmby Hills, California.

Christopher Polk /

Getty

“That’s the exact opposite of what makes Playboy Playboy,” Cooper says now, exasperated. “We should not apologize for sex.”

It’s a sentiment Hugh Hefner might have uttered in his heyday, when millions subscribed to his magazine and stayed up late to peer into his televised “penthouse.” For Cooper, the path forward in the era of online porn and cable-TV skin is to look back to the days when his father, writing in the first issue of his magazine, conjured the kind of guy who sought the company of women for “a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”

The son is sipping a Coke in the lounge of a swank hotel in Washington, D.C., where hobnobbing with power and the intelligentsia is another key part of Playboy’s strategy. Later, he and other company execs will huddle around a table at the White House correspondents’ dinner, the first one graced by Playboy. The group will dip out early, before Michelle Wolf cracks a single joke, to throw one of the buzzier parties of the weekend, featuring R&B crooner Miguel and a bunny-to-guest ratio hovering near 1:1. In June, the crew would return to attend the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Awards in the nation’s capital for the first time in its four decades, mingling with journalists and think-tankers at a Newseum reception.

Of course, the Playboy name has been bandied about Washington lately for more than just throwing a solid party. Both President Donald Trump and GOP money man Elliott Broidy have been prominently linked to former Playboy models whose silence was allegedly purchased at a high price. Reminded of this, Cooper winces.

“There’s a note that many companies and people live by, and that is ‘Any press is good press,’ ” the self-described liberal says dryly. “That’s (expletive).”

*****

Those who know Cooper say he was deeply affected by his father’s death.

“It’s motivated him even more,” says Kohn, “to bring this brand back to where it was 20 years ago,” better days for anyone in the skin business.

The question now is whether anyone cares.

“They went the direction of competing against Hustler, Penthouse, pornography, etc., forgetting that the nudity wasn’t the catalyst for Playboy,” says Susan Gunelius, a marketing expert and author of a book, “Building Brand Value the Playboy Way.” The company, she argues, forgot that ogling women was only ever supposed to be secondary to the cool-guy lifestyle Playboy espoused.

In trying to wipe away decades of spray-tan tarnish, Cooper has not hesitated to question some of his father’s choices. Hugh Hefner approved the move to end nudity. Cooper’s first audacious act was to bring back the flesh, enlisting his fiancee, “Harry Potter” actress Scarlett Byrne, to pose bottomless and pen a feminist-lite treatise on “freeing the nipple.”

One of the most obvious departures from his father’s aesthetic has been to promote more diverse beauty. Cooper calls the Playboy of five years ago “this factory for one particular look” – bleach-blond, orange-hued and scalpel-perfected.

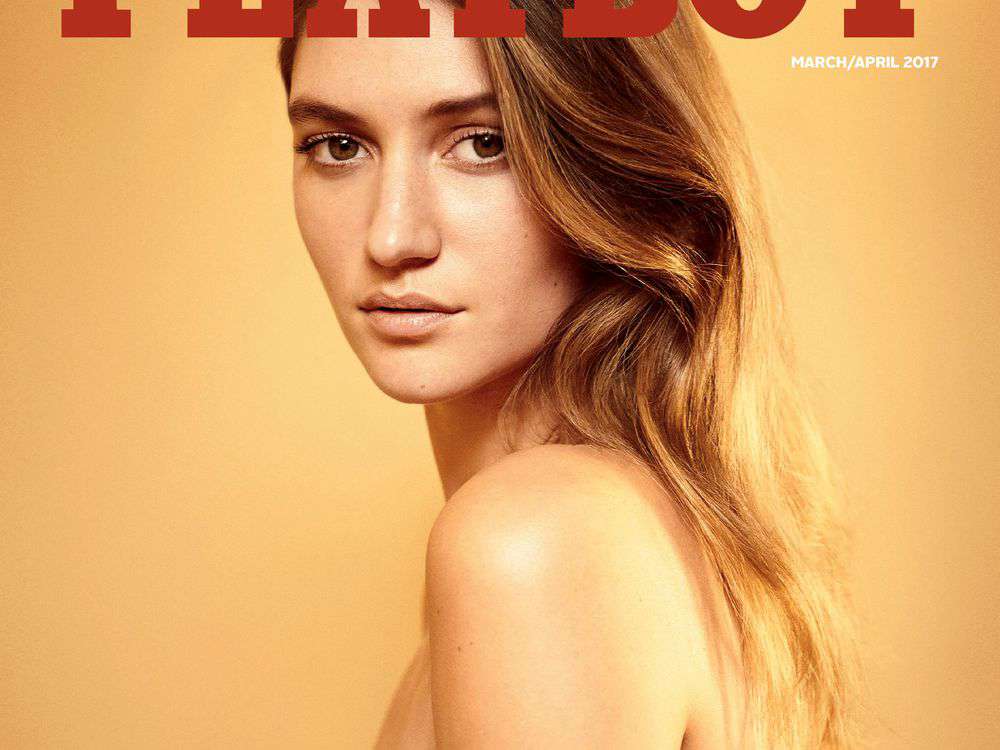

The March/April 2017 cover with model Elizabeth Elam announced the return of nudes to Playboy magazine. (Gavin Bond/Playboy)

Gavin Bond for Playboy /

Gavin Bond for Playboy

Nowhere was that Playboy look more codified than on “The Girls Next Door,” an instant hit that peeped into the notorious Playboy mansion and the lives of Hef’s blond, top-heavy sister wives. The reality show, which aired from 2005 to 2010, was a coup for Playboy because it managed to garner a largely female viewership – until the “girls” started appearing in the gossip rags with tales of drug use, Hef-mandated curfews and compulsory orgies.

Cooper, who says he hid from the show’s cameras as a child, is eager to relegate the show to ancient history.

Last fall, Playboy named French model Ines Rau the first transgender Playmate. It excised the phrase “Entertainment for men” from its spot on the cover for the first time since the magazine’s founding. In its place: “Entertainment for all.” The magazine also hired an executive editor, James Rickman, with edgy credentials from the high-design, cultishly followed Paper magazine.

Cooper’s colleagues, however, say the heir is the one who’s pushed the magazine to make an aesthetic leap away from Vaseline-screen retouching, and move toward more, uh, naturalism. Just look at the 2018’s Playmate of the Year, Nina Daniele, a bushy-browed, unaugmented hipster with a Penélope Cruz vibe. The Bronx native looks more like she’d grace the cover of an Urban Outfitters catalogue than Playboy, yet here she is.

But will any of it titillate millennials, who, despite the sexual revolution and porn and Tinder, don’t actually seem to have much sex?

“Which is fascinating,” Cooper interjects. “We’re not a generation that was introduced to sex or a masculine lifestyle by taking our dad’s Playboys,” he says. “Our experience (was) going online and seeing some incredibly graphic videos. … What does that do for an entire generation that was introduced to sex in that way?”

*****

Cooper’s mother, Playboy cover girl Kimberley Conrad, married Hugh Hefner in 1989, when Hefner was in his 60s and the Canada native was a tanned and leggy 28. Bill Cosby was among the guests at an affair celebrated with a pay-per-view special and a full-frontal pictorial replete with wedding-white lingerie. When they parted less than a decade later, Conrad and their two young sons (Cooper and his older brother, Marston, who doesn’t work for the company) moved next door – far enough from their father’s ever-growing cadre of girlfriends but close enough to maintain some semblance of family. It’s an arrangement Cooper now sees as a remarkable feat of co-parenting.

“I had a fantastic childhood,” he says. Though, yes, he acknowledges, “growing up at the mansion makes for a different experience than most people.”

Tell us everything and don’t skimp on the details, please.

There were flamingos in the backyard, he offers tersely. And fine, yes, of course there were Playmates.

“The parties went back to being wilder when my parents split up,” Cooper recalls. “It was always, ‘Keep the other house on lockdown so the boys don’t come over to Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ ” the mansion’s annual lingerie-required bacchanal.

Eventually, trying to rein in two warm-blooded teenage boys became an exercise in futility for his parents. So it was not a typical upbringing. Whose is, really?

It would be easy to see Cooper as just another scion of fame and wealth. His Instagram account is your average oversharing millennial’s, if that millennial had a private jet. There are cuddly photos with his fiancee, and glimpses of his work life, which seems to require being entwined with impossibly thin girls in corsets and bunny ears.

He counts among his friends the Nicholsons (Jack’s kids, Lorraine and Ray) and the younger Willises and Schwarzeneggers. Though Cooper told the Hollywood Reporter last year that Donald Trump’s long-ago appearance on a Playboy cover was “personal embarrassment” for him, Tiffany Trump was nonetheless in attendance at his New Year’s party. That’s just how heirs roll.

Playboy Chief Creative Officer Cooper Hefner speaks onstage at Playboy’s 2018 Playmate of the Year Celebration at Beauty & Essex on May 4, 2018 in Los Angeles, California.

Charley Gallay /

Getty Images for Playboy

Cooper, who started working for Playboy while an undergrad at California’s Chapman University, comes across as formal and practiced and older than his years. He’s at home in blazers and tuxes; his face brightens when talking about meeting Nancy Pelosi or posing for photos with CNN’s Don Lemon. He once mulled a run for Congress.

Hugh was something of a square, too – a married, Midwestern dad when he published his first issue in 1953, with old cheesecake shots of Marilyn Monroe he’d copped for $500. But he had a dream: to liberate 1950s sex from the bedrooms of marrieds, from shame and inhibition and boredom. He railed against puritanism, adopted a libertine attitude about monogamy and drugs and most everything else, and aimed his message squarely at the urban male. And before it all took on the oily sheen of lewdness, he may well have been the first to intertwine a brand so deeply with a lifestyle – his own.

What Cooper has most in common with her father, says his oldest child, Christie Hefner, is a creative vision. Forty years older than Cooper, she served as the company’s chief executive for all of his childhood; a skilled Hef whisperer, she’d long helped hold the financials together. But she stepped down in 2009, in the midst of the recession, a profound moment of crisis for all publishers.

The two speak weekly. And Christie says she can relate to the position Cooper now finds himself in. “From the day you join the company, everybody thinks that someday you’re going to run it,” she says. “That’s difficult.”

A few years ago, Cooper clashed with management over its ideas to remake Playboy as a safe-for-work site and left the company. (He owns only a limited, but undisclosed, share of the company.) “They didn’t know what they were doing,” he says pointedly. Playboy was an “adult brand. We’re not a BuzzFeed.”

He tried his hand at launching his own business, called Hop, that published nerdy blogs and promoted parties. Kohn urged him to return and help redirect Playboy – “not because he was a Hefner,” he says, “but because he understood what the brand was and what it should be.”

But would he ever embody the brand in the way his father did, swinging with a sea of nubile girlfriends? Cooper demurs.

“I’m engaged,” he says.

“Cooper is an intellectual,” says Kohn. “His father was a very serious person who liked to have a good time. Cooper has a lot of that DNA. But what he chooses to do with his social life is different. … He doesn’t need a number of girlfriends.”

That was Hef.

“That’s not Cooper.”

[ad_2]