[ad_1]

The salty fresh scent of the Pacific Ocean hangs in the air as a boat slices through the waters off northern Vancouver Island.

Some of the best scenery on the planet flashes by. Rocky islets covered with the dark green of dense Douglas firs. A pod of porpoises appears briefly in the boat’s wake before quickly diving out of sight.

The destination is a fish farm tucked away in a remote cove on Swanson Island.

Marine Harvest’s Swanson Island salmon farm was the scene of a recent standoff between indigenous protesters and the company. (Chris Corday/CBC)

For some, salmon farms are a blight on the landscape. Not for the way they look, but because of the threat they believe these large aquaculture operations pose to wild salmon.

“We’re pretty confident this place will have to be dismantled,” says Ernest Alfred, pointing at the farm from the boat. “And I’ll be here to watch it.”

The government is currently reviewing the leases of 20 fish farms that expire on June 20. Alfred and other opponents are upping the pressure on the NDP leadership in hopes they will commit to ending fish farming in the ocean. But supporters of the farms say that would be a huge blow to an industry worth billions of dollars to the province.

The B.C. Salmon Farmers Association says the province’s aquaculture industry generates $1.5 billion a year. (B.C. Salmon Farmers Association)

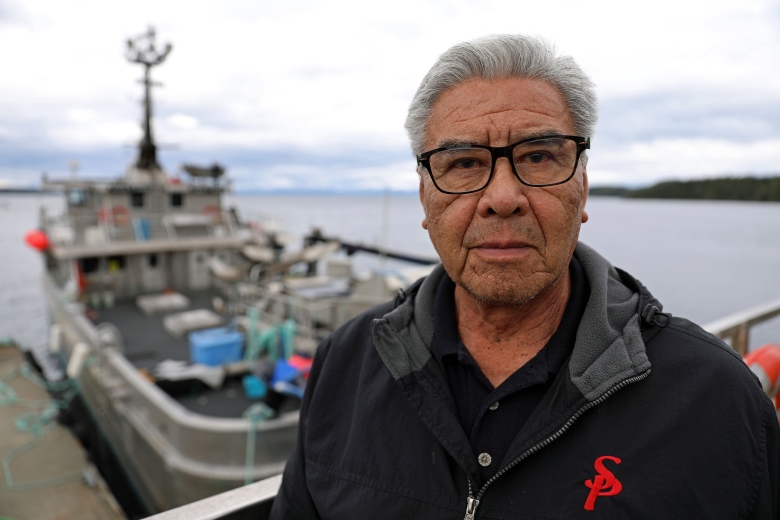

Alfred is a hereditary chief of the Namgis First Nation in Alert Bay, B.C., and he has the support of elected bands and councils in the area that oppose the farms.

He says the land and waters were never ceded, and he believes First Nations will ultimately gain control of the area. It’s a long-term battle still being fought in the courts and in negotiations with the federal and provincial governments.

“There is no such thing as reconciliation in this territory as long as these farms exist. They’re not welcome here. They don’t have social licence; they hardly have a legal stance.”

Table of Contents

ToggleDisease and parasites

Opponents fear the impact the farmed Atlantic salmon have on wild Pacific species.

The Atlantics are moved from hatcheries and placed into the ocean as young fish, or smolts. Nets suspended in the water prevent them from escaping. The farm’s buildings are usually on floating docks, and workers tend to the fish until they’re big enough to harvest.

A single operation can hold up to a million salmon.

Activist Alexandra Morton has been scrutinizing B.C.’s fish farm industry for three decades. (Chris Corday/CBC)

One big concern for opponents is a parasite known as sea lice. They attach themselves to the fish, weakening and sometimes killing them. Opponents are convinced the farms, with thousands of fish packed together, amplify the number of lice in the open ocean.

I’m 100 per cent sure these farms are killing off wild salmon,” says Alexandra Morton. She has been involved in this fight for 30 years, and has published research documenting the risks posed by the farmed fish.

Local First Nation members tried to stop Marine Harvest from restocking its fish farm on Swanson Island in March. (Swanson Occupation/Facebook)

“When you look everywhere in the world, Norway, Scotland, Ireland, Faroe Islands, Eastern Canada, Western Canada, wild salmon go into precipitous decline as soon as this industry operates.”

However, the industry says wild stocks fluctuate and there is no conclusive evidence declines are caused by farmed fish.

Another risk, Morton says, is the spread of piscine orthoreovirus (PRV), which can cause heart and muscle inflammation in infected fish.

There is emerging scientific evidence linking the spread of the virus from farmed Atlantic salmon to wild Pacific salmon.

‘Bad behaviour’

There are about 50 active fish farms in B.C. waters.

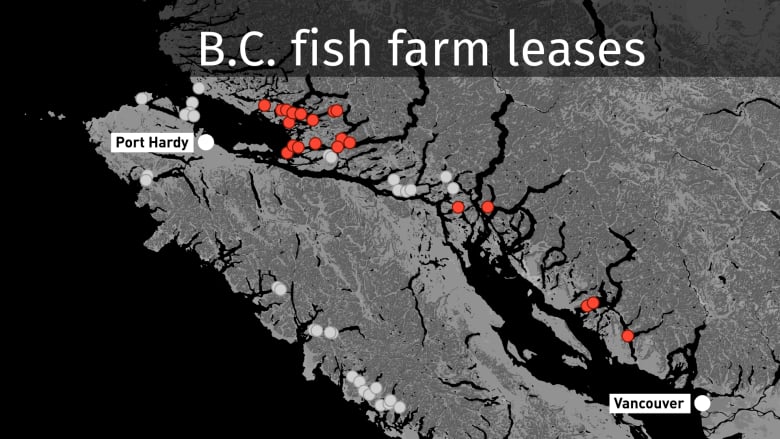

At the moment, activists are trying to convince the government not to renew permits at 20 sites. The farms are concentrated in the Broughton Archipelago, near northern Vancouver Island, a key migration route for many salmon runs.

Morton says if the one-year-old NDP government renews the leases it will send the wrong message.

“It’s like enabling a drug addict. They can just keep on with this bad behaviour. But if you stop the tenures, then they’re going to have to figure out what they’re going to do and we can get busy with restoring these wild fish.”

Locations of fish farms in B.C. The ones in orange are up for renewal with the provincial government. (CBC)

Morton says the companies could move to land-based farms, where the fish and their effluent are contained.

She and other opponents are buoyed by action in Washington state, which has effectively banned the farming of Atlantic salmon in its waters.

Support for fish farms

Jeremy Dunn, head of community relations for Marine Harvest Canada, a branch of the world’s largest aquaculture company, Marine Harvest, based in Norway, says the idea that the millions of Atlantic salmon now being reared in net pens in the ocean could be easily moved to large tanks on land is not realistic.

“There have been people working to try and perfect growing salmon to market size in tanks for 30 years, and no one’s been able to make a sustainable business out of it,” he says. “A lot people have lost a lot of money.”

Jeremy Dunn of Marine Harvest Canada says moving fish farms onto land is still not a financially viable option for companies. (Chris Corday/CBC)

Approximately $1.5 billion in revenue and 6,600 jobs in the province are tied to the industry, he says.

“We know how to keep our fish healthy, we know how to ensure that we are mitigating any potential risk, and we know that we can coexist alongside a healthy wild fishery and help conserve Pacific salmon.”

Jobs in remote communities

Simon Paul, one of 65 workers at Hardy Buoys, a commercial smokehouse in Port Hardy on Vancouver Island, says steady employment is helping him in his recovery from alcohol addiction.

“That’s why it’s important to be at work every day, and I enjoy what I do here,” he says, lifting large trays of bright red-orange chunks of smoked salmon.

Simon Paul, a worker at the Hardy Buoys Smoked Fish processing plant, says B.C. needs fish farming to provide jobs. (Greg Rasmussen/CBC)

Bruce Dirom owns Hardy Buoys, which processes both farmed and wild products. He says having fish year-round has allowed him to boost production.

“With farmed salmon it’s a lot easier for us to buy fresh and keep the product flowing.”

He says he “would have to close the doors” without the farmed Atlantics.

Indigenous support for farms

Docked outside the Marine Harvest processing plant in Port Hardy, James Walkus explains that he owns a fleet of nine boats, and although some are used to catch for wild salmon, he’s increasingly invested in special boats used to transport the farmed fish to processors.

“There are a lot of us First Nations … that are for it,” he says of fish farming.

James Walkus owns large commercial fishing vessels, and also transports salmon from the farms for Marine Harvest. (Chris Corday/CBC)

Salmon farming and its related industries employ many Indigenous workers, he says, and he’s confident more farms could be built safely on the B.C. coast.

Ending the leases, he says, “would be absolute devastation to the industry.”

The provincial government has so far kept quiet about its plans for the leases, but on Friday it announced a new Wild Salmon Advisory Council to research and report back on measures needed to protect wild fish.

Alexandra Morton says it’s not fish farming per se that’s the problem, just the way it’s currently being done.

“Nobody is saying no aquaculture,” she says.

“They’re just saying you can’t kill our wild fish while you’re growing yours.”

[ad_2]